Archaeologists have discovered the purpose of fragments of rope unearthed during excavations at an abbey in Nottinghamshire. The pieces were found at Rufford Abbey in 2014 but were not fully understood until they were compared with an item on show at Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire.

It turns out the ropes, made from woven copper alloy wires, are parts of a scourge, used by medieval monks as a self punishment, or to cleanse the soul.

Scourge use increased in the 14th century after the Black Death swept through the country. People believed the plague was a divine retribution for earthly sins and chose to punish themselves to earn god's blessing.

Rufford Abbey, first built in the 12th century, is now used as a country park. The scourge ropes were discovered during a dig in the meadow near Ollerton.

Wednesday 30 March 2016

Friday 25 March 2016

Bonnie Prince Charlie

In 1745 Bonnie Prince Charlie (Charles Edward Stuart) led a rebellion in a bid to restore the British Throne to the House of Stuart. With the support of Highland clansmen he headed south and reached Derby before being beaten back. (He was finally defeated at the Battle of Culloden and fled to France with a price on his head.)

However, during his campaign southwards he stayed in Ashbourne in Derbyshire, and while there he declared his father to be the rightful king - James III.

For such a significant event in history there is remarkably little to mark the spot where it happened. There is a very subtle plaque on a wall in the market place, which would be very easy to miss. In fact it is almost overshadowed by a second plaque marking the death of one Tom Fearns, aged 40, who died in 1930 after the balance bar of the town fire bell broke and hit him.

However, during his campaign southwards he stayed in Ashbourne in Derbyshire, and while there he declared his father to be the rightful king - James III.

|

| Bonnie Prince Charlie statue in Derby |

Saturday 12 March 2016

Annesley Old Church

Not far from junction 27 of the M1 you'll spot a ruined church surrounded by an abandoned burial ground. This is the 14th century Annesley Old Church, a Grade I listed scheduled ancient monument. There's not much of it left, but what remains shows just how fine the original must have been.

The church was built by the Annesley family in 1356 to replace a Norman chapel on the same site. It was in use for some services as late as the 1940s, although a parish church serving the nearby mining village of Annesley was constructed in 1874.

The church's state of repair meant it was listed on the Heritage At Risk register. It is currently owned by Ashfield District Council and a band of conservation supporters have launched a preservation project with the help of a £450,000 Heritage Lottery grant.

On the south wall is a triple sedilia (seats for use by the officiating priest and his assistants during communion services) and a piscina (shallow bowl used to wash communion vessels). The art historian Nikolaus Pevsner believed they predated the church and had been brought in from some other building.

There are also remains of a Norman arch from the original chapel and remnants of decorative nail head mouldings around the top of one of the pillars.

Both Byron and D H Lawrence (two local writers) mention the church. The estate passed by marriage to the Chaworth family in the 17th century. Byron and Mary Ann Chaworth were sweethearts and she is named in two of his poems.

Hills of Annesley, Bleak and Barren,

Where my thoughtless Childhood stray'd,

How the northern Tempests, warring,

Howl above thy tufted Shade.

Now no more, the Hours beguiling,

Former favourite Haunts I see,

Now no more my Mary smiling,

Makes ye seem a Heaven to Me.

Lawrence describes it in his 1911 novel The White Peacock.

The church is abandoned. as I grew near and owl floated softly out of the black tower. Grass overgrew the threshold. I punched open the door, grinding back a heap of fallen plaster and entered the place. In the twilight the pews were leaning in ghostly disorder, the prayer books dragged from their ledges, scattered on the floor in the dust and rubble, torn by mice and birds. Birds scuffled in the darkness of the roof.

The church was built by the Annesley family in 1356 to replace a Norman chapel on the same site. It was in use for some services as late as the 1940s, although a parish church serving the nearby mining village of Annesley was constructed in 1874.

The church's state of repair meant it was listed on the Heritage At Risk register. It is currently owned by Ashfield District Council and a band of conservation supporters have launched a preservation project with the help of a £450,000 Heritage Lottery grant.

On the south wall is a triple sedilia (seats for use by the officiating priest and his assistants during communion services) and a piscina (shallow bowl used to wash communion vessels). The art historian Nikolaus Pevsner believed they predated the church and had been brought in from some other building.

There are also remains of a Norman arch from the original chapel and remnants of decorative nail head mouldings around the top of one of the pillars.

Both Byron and D H Lawrence (two local writers) mention the church. The estate passed by marriage to the Chaworth family in the 17th century. Byron and Mary Ann Chaworth were sweethearts and she is named in two of his poems.

Hills of Annesley, Bleak and Barren,

Where my thoughtless Childhood stray'd,

How the northern Tempests, warring,

Howl above thy tufted Shade.

Now no more, the Hours beguiling,

Former favourite Haunts I see,

Now no more my Mary smiling,

Makes ye seem a Heaven to Me.

Lawrence describes it in his 1911 novel The White Peacock.

The church is abandoned. as I grew near and owl floated softly out of the black tower. Grass overgrew the threshold. I punched open the door, grinding back a heap of fallen plaster and entered the place. In the twilight the pews were leaning in ghostly disorder, the prayer books dragged from their ledges, scattered on the floor in the dust and rubble, torn by mice and birds. Birds scuffled in the darkness of the roof.

Saturday 5 March 2016

Cows

A couple of weeks ago I had to pass a couple of hours in Stoke on Trent while the Other Half visited a friend in hospital, so I dropped in to the Potteries Museum.

It's a great place, with several important artefacts, but one of the most popular exhibits is the Keiller collection of 667 cow creamers. The jugs were gathered over 30 years by Alexander and Gabrielle Keiller (the marmalade family). The ceramics were presented to the museum in 1962.

Cow creamers are basically milk jugs in the form of a cow, with a hole in the back to fill the jug, and a hole in the mouth to pour through.

The earliest examples in Britain were Dutch imports made in silver, but by the mid 18th century the Staffordshire potters were copying them in ceramic. Eventually their popularity grew and they were made all over Great Britain, well into the 19th century.

The majority of the Keiller Collection were manufactured in the second half of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century.

I own a modern cow creamer that I bought from M&S a few years ago but it's nowhere near as fancy as the ones at the museum. For example, I particularly liked this one on the right - catalogued as Garten Bos. According to the museum website it dates from around 1820 and was made in Glamorgan, South Wales.

It's a great place, with several important artefacts, but one of the most popular exhibits is the Keiller collection of 667 cow creamers. The jugs were gathered over 30 years by Alexander and Gabrielle Keiller (the marmalade family). The ceramics were presented to the museum in 1962.

Cow creamers are basically milk jugs in the form of a cow, with a hole in the back to fill the jug, and a hole in the mouth to pour through.

The earliest examples in Britain were Dutch imports made in silver, but by the mid 18th century the Staffordshire potters were copying them in ceramic. Eventually their popularity grew and they were made all over Great Britain, well into the 19th century.

The majority of the Keiller Collection were manufactured in the second half of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century.

I own a modern cow creamer that I bought from M&S a few years ago but it's nowhere near as fancy as the ones at the museum. For example, I particularly liked this one on the right - catalogued as Garten Bos. According to the museum website it dates from around 1820 and was made in Glamorgan, South Wales.

Tuesday 1 March 2016

Crossing the line

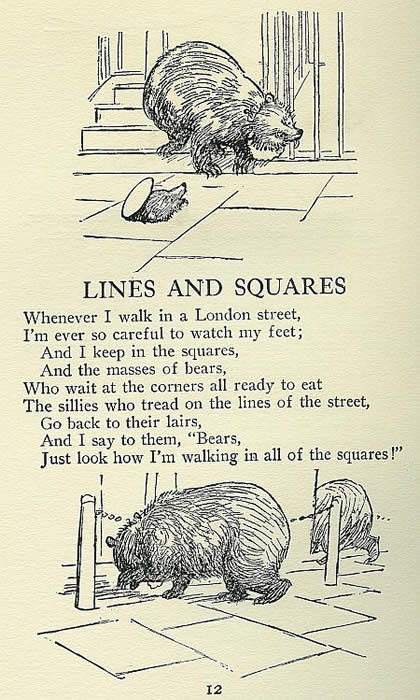

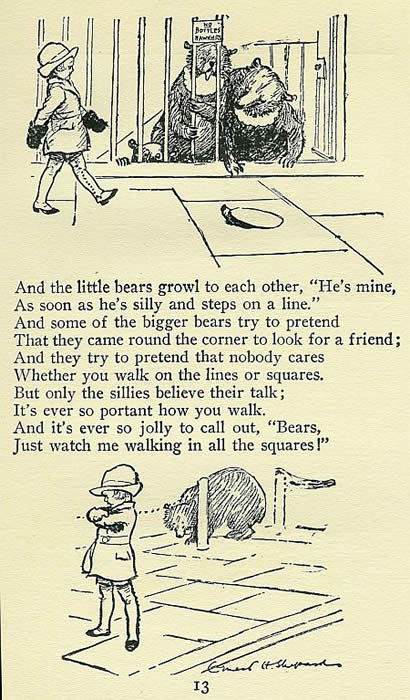

And the little bears growl to each other "He's mine,

As soon as he's silly and steps on a line."

Have you ever heard the expression "he's living on the edge"? And have you ever considered what it actually means? There's an obvious interpretation, that someone too close to the edge is in danger of falling, but there is a much more complex idea behind the concept of edges: liminality.

The word derives from the Latin for threshold and has been adopted by anthropologists to describe events in people's lives and the rituals and traditions associated with them. Liminality is neither one place nor another - the junction between two known factors, where one fades to another but there is no definite boundary. For millennia this state of 'betweenness' has been associated with potential danger, and so mankind has surrounded himself with rituals designed to protect those passing from one state to another: rites of passage, steeped in tradition, that must be followed to the letter.

Often people are unaware of the reason for their actions at such times. Think weddings, for example. It is important for the bride to have 'something old, something new, something borrowed and something blue'. But why? Any book of folklore will list hundreds, if not thousands, of similar examples, and the origin of most is lost in time. From childhood to adult, from single to married, from life to death, each stage is marked by movement across some form of threshold. Those changes are associated with special rituals, baptism, marriage, initiation or funeral rites. Ancient humans saw these times as part of the soul's journey through life. Such boundaries were risky, fraught with danger, because the soul did not belong in either place until the change was complete.

The something old, something new, something borrowed and something blue are not just to ensure a long and happy marriage. It is significant that the bride must have the four elements on her wedding day but does not need them afterwards. They are therefore to protect her before the ceremony takes place. Once she is in the gown and on her way to be married she is no longer a part of her original family but has not yet joined her new one. It is for that time that she needs the talismans.

Similarly the rituals of death are mostly associated with the time that the corpse is above ground or before it is consigned to the fire. Covering mirrors, sitting with the corpse, lighting candles and the hundred and one other rituals observed by the Victorians before a funeral were designed to ensure that the spirit would rest easy. To make sure that the soul did not wander the earth because it had no proper "send-off". The burial, headstone and inscriptions ensured that the body stayed where it was put, the other observances were to guarantee that the soul went on its way and did not hang around to hamper the living.

The belief spilled over onto the physical world too. Think about horsehoes hung above doorways to keep out evil from the home; captains being piped aboard ship; taking off your shoes before entering a house, the hazards of stepping on a line on the pavement. How many folk tales involve bridges and the possible dangers that lurk as you cross? The Three Billy Goats Gruff risked a troll's anger as they tripped across their rickety-rackety bridge. A tale associated with Devil's Bridge in West Wales tells how the Devil agreed to build a bridge across the very deep ravine in exchange for the soul of the first creature to cross it. The very clever woman who lived next to the crossing sent her dog ahead of her on the first journey, so the Devil left without the human prize he'd hoped for. Many cultures believe that evil spirits cannot cross bridges.

So take care next time you're out in the street and never forget: It's ever so portant how you walk.

A.A. Milne. 1925

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)